VMware sponsored this post.

Is a company a good citizen of open source communities or guilty of “openwashing”? The question gets asked almost anytime a corporation markets a product as open source or announces that software has been open sourced. Along with The Linux Foundation’s TODO Group and VMware, InApps has conducted research about open source in the enterprise that provides data and a framework to answer the question.

The study identifies corporate contributions, collaboration with others, and leadership as key metrics of open source citizenship. It then gauges how the community views 11 companies’ open source citizenship, according to these metrics. We surveyed 2,700 people and the vast majority use open source to some degree, and half work at companies that frequently use open source in commercial products.

With data about contributions, collaboration and leadership in hand, we show how respondents’ own employers measure up to these benchmarks. The resulting analysis provides insight into how open source users of varying degrees perceive a company’s open source involvement and how that affects their company’s employment or buying decisions. Their responses have important implications for the sustainability of open source ecosystems and how open source communities can measure and define good corporate citizens.

Key findings:

- Google’s open source brand is stronger than its peers.

- Compared to all respondents, the most active upstream contributors view Microsoft and Intel more positively; the opposite is true for AWS.

- Companies deeply involved with the community make buying decisions that are significantly influenced by a vendor’s open source citizenship.

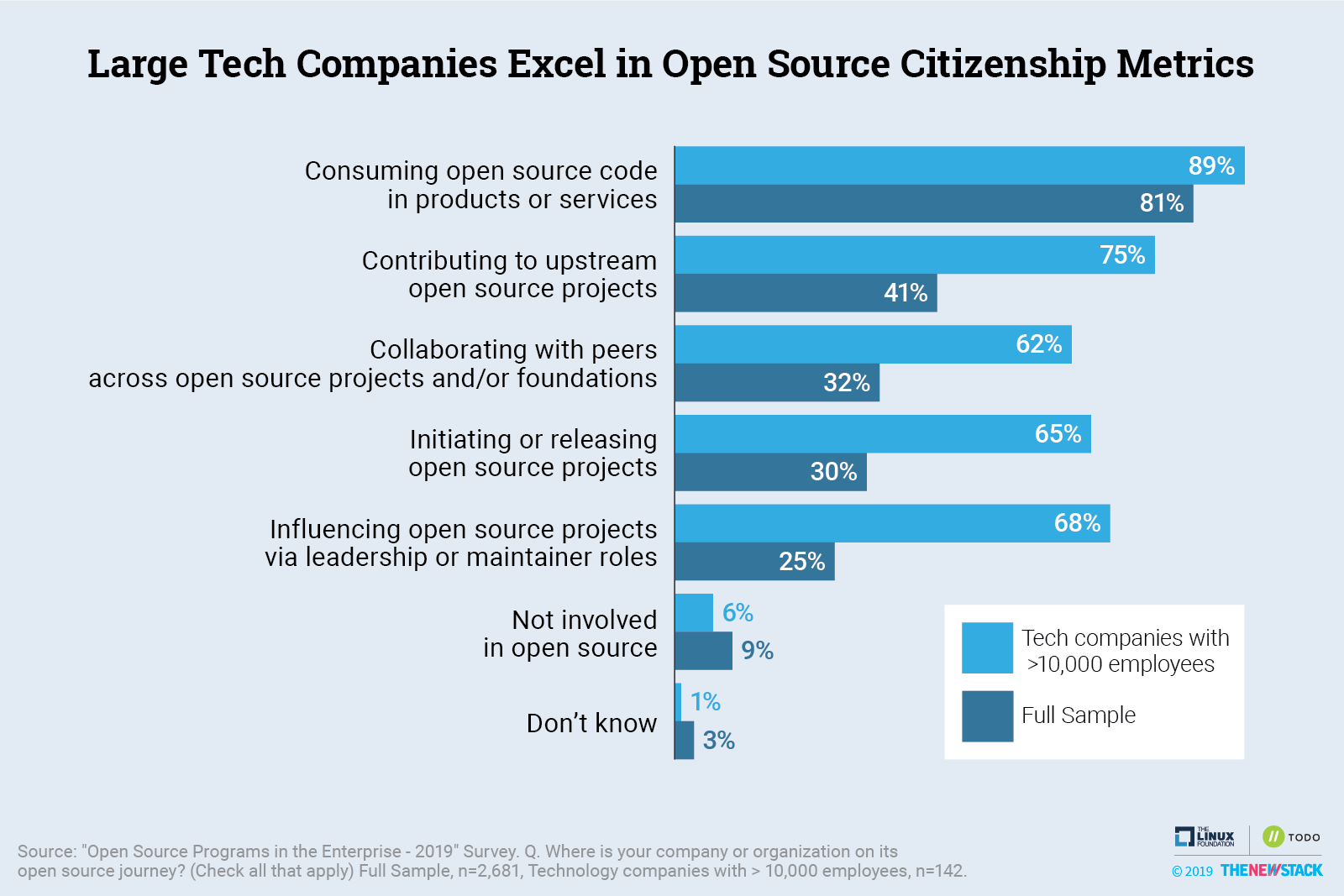

- Large tech companies are most likely to be actively involved in open source ecosystems; 75% contribute to projects upstream, compared to 41% for the overall study.

Perceptions

“To what degree do you perceive the following companies to be ‘good open source community citizens’ in terms of their contributions, collaboration and leadership on open source projects and initiatives within the open source ecosystem?”

We asked respondents this question about 11 TODO Group members, which represent a broad cross-section of technology companies. All TODO Group members have a significant investment in open source and many have dedicated open source programs to set policies and encourage contributions. Although many of the companies we asked about received mediocre ratings, others performed well. We expect to see shifts in perception when this new question is included in future studies.

Companies with a history of open source commitment are more likely to be perceived as good open source citizens. Topping the list is Google, with twice as many respondents saying Google’s citizenship is excellent as compared to the next best company. Overall, 72% rated Google as either excellent or above average. Android, Kubernetes and TensorFlow are just some of the popular projects that originated at Google, and the company contributes to hundreds of more projects outside of its purview.

Next on the list are IBM, Microsoft, Intel, Facebook and Pivotal, all of which received more positive as compared to negative ratings.

IBM’s researchers have been contributing to open source for a long time, and would likely have fared well in this study even without its acquisition of open source behemoth Red Hat. Like IBM, Intel has historically contributed to Linux-related projects.

Despite public relations hurdles, on average, Microsoft and Facebook are viewed positively. Still, 28% view Microsoft as a below-average or poor open source citizen. Veterans of the Linux versus Windows wars, especially those who work for smaller businesses, still hold a grudge against Microsoft and are quick to note that many of its open source projects are embedded into a larger ecosystem that it monetizes. Facebook’s challenges are mostly due to consumer-related privacy concerns rather than how it supports open source projects.

The Undecided Vote

Many people don’t have an opinion on a company’s open source citizenship, with more than half of the study answering “don’t know” about four vendors. One reason for this lack of opinion is brand awareness. For example, web developers may not know about Pivotal because the company is focused on infrastructure software offerings. Comcast has a strong consumer brand; however, it has limited exposure to the open source community as compared to the other companies that actually sell and support technology solutions.

Despite Salesforce and SAP’s prominence as software giants, a high percentage couldn’t provide an opinion about these companies, either. This is proof that much of the community doesn’t automatically classify proprietary software vendors as anti-open source. Unfortunately, twice as many of the remaining respondents have a negative perception of the corporations’ involvement in open source as compared to a positive view.

Factors Influencing Perception

Both Amazon Web Services and VMware have slightly more detractors as compared to those who believe they are good open source citizens. Yet, a large segment of the open source electorate is still forming its opinions about these companies. The study found some clues into what is influencing perception about these companies.

In general, the open source community remains skeptical of corporate motives.

Like Facebook, AWS is a widely known brand that faces growing criticism among the general public. Developers and technology professionals have more exposure to AWS, and the consensus is that AWS generally provides quality services at competitive prices. If respondents only judged AWS based on price/performance, the company should get glowing reviews. The data presents more of a mixed picture because it represents the views of the open source community.

In general, the open source community remains skeptical of corporate motives. Only 37% of respondents’ gave vendors a positive rating on average, while 56% had ratings that skewed towards poor or below average. Even if a corporation is deeply involved with open source projects, some pessimists will claim that this is only because of an ulterior motive as opposed to dedication to social responsibility or an open source ethos.

Discounting the views of eternal pessimists and the anti-business crowd, there are still real reasons to be suspicious that a company’s supposed altruism is really a bet on growing a company’s market share. Dirk Hohndel, vice president and the chief open source officer at VMware, acknowledges that enlightened self-interest plays a role in open source contributions, but believes that “a good open source citizen is someone who has teams that contribute purely based on the good — on the desires of the project.”

A segment of the open source community is particularly hostile to AWS because it is supposedly a taker instead of a maker. The argument is that AWS uses open source code in its products but doesn’t dedicate significant resources to projects that are beneficial to the entire community. Furthermore, AWS is accused of threatening the viability of startups that rely on a so-called open source business model.

Current and aspiring founders of open source startups are among the most credible voices talking about open source citizenship. However, there is little proof that having a business plan based on open source is strongly correlated with actual open source community activity.

A fifth of our survey sample can be considered to be active open source community members because they work at a company that frequently contributes code to upstream projects. This group takes a dimmer view of AWS, with 44% having a negative outlook on its open source citizenship as opposed to 28% having a positive view. In contrast, active community members’ opinion of Microsoft and Intel rises significantly, possibly because they have been seen doing hands-on work to support open source projects.

Changing Perception Takes Time

More people view VMware’s open source citizenship negatively (27%) than positively (22%). Hohndel acknowledges VMware has room for improvement but is encouraged by the results. He told InApps, “That’s certainly an improvement from where we were years ago.” His philosophy is that changing perception is a long-term process. As the leader of the company’s Open Source Program Office, Hohndel makes sure that people new to the open source space see that VMware is engaged with a lot of upstream projects and is actively contributing to projects it cares about. By sponsoring this survey with InApps, VMware aims to gain insight on how it can improve and set baseline metrics for future studies: They want to measure how they improve over time.

Hohndel is hesitant to put too much value into the marketing and branding of corporate open source activity. Citing his background as a software developer, Hohndel said, “I really believe that we need to lead with good work, good contributions, good citizenship in the project. Then, later on, it matters how you market it and how you talk about it.”

Measuring Good Open Source Citizenship

Determining if an individual is a citizen is the source of ongoing political controversy throughout the world. Defining corporate citizenship is also difficult, but we like this explanation from a research unit at Australia’s Deakin University:

“Corporate citizenship is a recognition that a business, corporation or business-like organisation, has social, cultural and environmental responsibilities to the community in which it seeks a licence to operate, as well as economic and financial ones to its shareholders or immediate stakeholders.”

Open source is both a community unto itself and a component of the larger society and economy. Even firms that never use open source software benefit from the economic productivity it generates. Users of open source can be regarded as passive citizens, with a stake in the laws governing its use. Individuals that contribute to open source projects are more active citizens.

Companies get involved with communities when they support projects. This support can take the form of direct funding, adopting standard licenses and practices, and allowing employees to participate in projects during work hours.

It is a daunting task to measure a company against subjective lists of responsibilities. But that didn’t stop us from trying. For the purposes of the survey, “good open source community citizens” are measured in terms of contributions, collaboration and leadership on open source projects and initiatives within the open source ecosystem. These metrics discount activity that can be seen as being narrowly self-interested.

InApps sought to benchmark the current state of open source citizenship based on actual participation. The survey’s first question asked respondents about where their company is on its open source journey. Since 81% of respondents’ companies use open source code in products or services, we decided this is not a valuable differentiation. The study also found that 30% of respondents’ companies are initiating or releasing open source projects. This does not accurately reflect good citizenship because the projects may have little or no impact on the larger community. We instead focused on the following measures of open source community involvement:

- Contributions: 41% of respondents’ employers contribute to upstream open source projects. This indicates that development work can be shared by the larger community and not just a single company.

- Collaboration: 32% of respondents’ employers collaborate with peers across open source projects and/or foundations. The trust needed for collaboration reduces often intangible transaction costs that is a key aspect of behavioral economics analysis.

- Leadership: 25% of respondents’ employers influence projects via leadership or maintainer roles. Despite complaints that corporations are unduly influencing community decisions, they also give their staff time to perform the less glamorous, janitorial activities critical to the success of an open source project.

Other Measurement Approaches

Open source citizenship can also be measured based on the extent to which open source code is used. A US government pilot program, which requires all agencies to release at least 20% of its new custom-developed code as open source, suggests the following metrics: lines of code; number of self-contained modules; cost; number of software projects; and system certification and accreditation boundaries. Enforcing the rule will be difficult. Despite disagreements about what types of licenses are truly open source, identifying usage patterns of licenses is not the biggest challenge. Instead, determining what parts of the entire stack should evaluated is a source for concern. For example, if you use Kubernetes and Linux, the thousands of lines of code in these projects could possibly be counted.

The availability of statistics from GitHub and other code repositories has made it easy to rudimentarily gauge corporations’ involvement in open source projects. InApps itself used enriched GitHub data with additional information about corporate involvement for its analysis of the Docker ecosystem. (see Page 52 of our eBook “Applications and Microservices with Docker & Containers”). More recently, assessments of the Kubernetes project show that VMware and other companies have started to represent a larger percentage of the project’s contributor base. These approaches have their merits, but are difficult to apply because each company and project’s practices are unique. To learn about using statistics to evaluate projects, we recommend reviewing what the CHAOSS (Community Health Analytics for Open Source Software) project is doing.

Profiling the Most Involved Community Members

Seventeen percent of all survey respondents work at companies that are concurrently contributing, collaborating and leading open source projects. These companies are likely to have several policies meant to support the open source community at large. For example, 71% of survey respondents’ companies are a member or sponsor of an open source foundation, while the study’s average is 23%. Furthermore, 51% have a program to reward and recognize open source contributors, inside and outside of their organization, compared to the study average of 18%.

The survey data finds that large technology companies are more likely than any other segment investigated to be involved in open source ecosystems. Of the 142 large tech company participants in the study, 56% say their company is contributing upstream, collaborating with peers and influencing projects via leader or maintainer roles. Although large tech companies supply a lot of developers to open source development, this is sometimes just a small percentage of all the developers working within an enterprise.

Impact of Good Open Source Citizenship

Debates about corporate social responsibility (CSR) only matter if they impact economic activity. Just like environmental activists, open source proponents have been waging a long-term battle to change attitudes and behavior. Most consumers claim to care about the environment, but price, convenience and quality have historically been prioritized in buying decisions. The same decision matrix applies to software, and open source often makes credible claims that it is superior based on the merits. While the analogy is not perfect, we see that just like with the environment, a segment of the community is making decisions based on soft, “social responsibility” issues. In this section, we will review how good corporate open source citizenship is impacting what software is used and where developers are deciding where to work.

We previously reported that there is no consensus about whether or not a company’s contributions and participation in the open source community have an impact on buying decisions. Thirty-two percent of the survey said that a company’s participation in, and contribution to, the open source community was only slightly or not at all influential on their organization’s buying decisions. On the flip side, 29% say it is extremely or very influential. Another 23% noted a moderate influence.

We took a deeper look and found good news for companies that believe they are solid members of the open source community. Across the board, respondents that believe a company’s community participation is important to buying decisions are also more likely to believe specific companies are good citizens. Notably, among the 29% that believe citizenship is at least very influential, both AWS and Intel see a seven percentage point increase in citizenship ratings compared to the study average. This is a sign that some market pessimism can be dismissed as coming from skeptics that won’t make buying decisions based on their attitudes.

In contrast, companies actively working with others in the open source community are more likely to consider open source activity when they choose a vendor. Thus, 40% of companies that collaborate with peers across projects and or foundations say citizenship is at least very influential in buying decisions, an 11 percentage point increase compared to all respondents. Companies that are initiating or leading projects are also likely to say citizenship affects buying decisions.

Corporate open source citizenship may have an even bigger impact on recruitment of future employees. A 2018 survey by Dice and The Linux Foundation found that among companies that hire “open source developers,” 48% financially support open source projects at least in part to to help with recruitment. Our data shows that 38% of respondent’s employers are at least sometimes recruiting developers to work on open source projects, and 35% are at least sometimes training developers to contribute to open source projects.

The data demonstrates that companies with the most mature open source practices are also the most likely to be hiring developers with experience working on open source projects. For example, 64% of companies that regularly contribute code to upstream projects also regularly (sometimes or frequently) recruit and hire developers to work on open source projects. The figure is 27% for everyone else.

We also know that companies that train developers to contribute to open source are almost twice as likely to be actually contributing to an upstream project.

Demonstrating strong community involvement should have a positive impact on hiring. The aforementioned 2018 study described ways employers can attract open source developers. Most effective is providing opportunities for training and attending conferences. Close behind is giving developers time to work on open source projects and providing clear policies about that contribution. Our recent survey found that companies that have an open source program office (OSPO) are more likely to have many such policies. Notably, 59% of companies that say increased developer recruitment and retention is a benefit of their OSPO have a program to reward and recognize open source contributors. In comparison, only 18% of the study operate such initiatives.

Anecdotally, we know that developers want to work for a company that is a good open source citizen. Future research is needed to determine how this plays into decisions about where to work, alongside factors like salary, the opportunity to work on new and exciting projects, and work/life balance.

Conclusion

Perhaps the biggest benefit of being a good open source citizen is how it can help transform how a company operates, from technology adoption and licensing practices, to policies, recruiting and hiring. It can also transform how technology is shared and developed internally to increase developer productivity and lower development costs, a practice sometimes described as inner sourcing. VMware’s Hohndel warns companies about investing in open source projects focused on tangential parts of the technology stack. Instead, companies should decide which software components are critical to your business and help differentiate your offering.

Overall, the ability to hire and maintain developers may be the biggest benefit of open source citizenship. Furthermore, the companies most involved with the open source community are inclined to make buying decisions based on community involvement.

Marketing and spinning your open source involvement will have limited value in the long-term because developers are skeptical and can see through openwashing. Instead, focus on the hard work of building out the three metrics of good open source citizenship: contributions, collaboration and leadership.

Methodology: The survey was conducted on July 8 – 29, 2019 and over 2,700 responses were received. Respondents were solicited via social media and with emails to The Linux Foundation, TODO Group, and InApps email lists. The full dataset can be found here.

The Linux Foundation, Oracle, and Pivotal are sponsors of InApps.

Feature image: Raphael’s “School of Athens”

InApps is a wholly owned subsidiary of Insight Partners, an investor in the following companies mentioned in this article: Docker.